Would collaborative purchasing provide better access to market for women farmers while making life easier for consumers in the busy capital of Kenya?

That was the questions we asked at the beginning of our SIANI Expert Group project.

Collaborative purchasing is an idea that customers will purchase food available for sale on a website together with others. It is built around a simple proposition: ‘If you can buy with a neighbour or people in your vicinity, then you can transport it together’, or in other words, purchase collaboratively.

However, quite early on we learned that this concept would be difficult to implement in Nairobi for a number of reasons. The biggest one is that smallholder farmers aren’t keen on focusing on individual household buyers because they typically make small purchases and the associated delivery costs make them less attractive.

Instead, smallholder women farmers are more interested in accessing large buyers who make regular medium to large orders – the consistency of these customers enables farmers to generate more income and plan their production and sales further ahead.

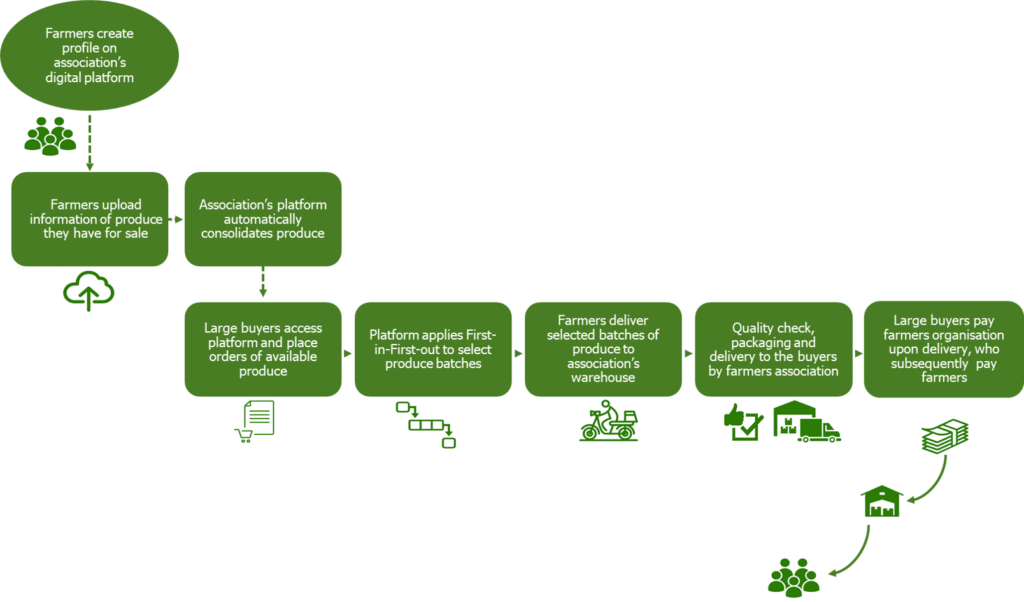

Also, during our field study many of the smallholder farmers indicated they would appreciate the opportunity to have a simple solution which would help them work with other farmers to sell their produce collaboratively in an easier more accessible way. So, that is how we arrived at the concept of collaborative selling vs collaborative purchasing.

Collaborative selling could provide smallholder farmers with the capacity to consistently meet required quantities and quality of orders, a key barrier standing between them and the large buyers.

In turn, the large buyers, such as exporters and restaurants who we interviewed during the study, felt they would need quality assurance of produce purchased from smallholder farmers, particularly when crops from different farmers were combined. They were also interested in a solution which would enable them to efficiently locate fresh produce they needed from smallholder farmers.