Our food systems are broken. The good news is that we know what to do about it, and we have for a long time. The Limits of Growth, published in 1972 by the Club of Rome, described the Green Revolution as a technological solution to the world’s food problems, overlooking its social and environmental consequences. Mirroring the gross domestic product (GDP), which was described by Robert F. Kennedy as an indicator that ‘measures everything except that which is worthwhile‘, food systems have been driven by a lust for productivity, measured in yield per hectare, lacking indicators that could consider socio-cultural and environmental aspects integral to providing healthy nutrition for all. Today, negative aspects of food systems contributing to GDP growth include the productivist expansion of cultivated lands without regard for the ecosystem destruction they incur, the lobbying of the agro-industries maintaining structural power imbalances and the health-care costs of immuno-deficiencies afflicting people around the world. At the same time, we are failing to account for both the negative and positive impacts of our food systems. The State of Food and Agriculture 2023 unveils some of what was left unaccounted for, estimating the hidden costs of food systems to reach at least $10 trillion a year, representing about 10% of the global GDP.

Against this background, the need for new economic indicators is blatantly clear, as is the need to re-think our food systems beyond the sole pursuit of economic growth.

Agroecology – a long-awaited fix to our food systems

In the footsteps of the 2002 Rio+10 Summit on Sustainable Development, an international assessment of global agriculture was initiated by the World Bank and the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO). The landmark report that followed “Agriculture at a Crossroads”, also known as the IAASTD report, conveyed a clear message calling for a radical transformation of food systems towards an agroecological model.

Drawing evidence from across the world, the report’s authors concluded that maintaining the status quo was not viable, paving the way for a paradigm shift. Emphasising the need for solutions that tackle the cause of the problems rather than the symptoms, this new paradigm builds upon the recognition of planetary boundaries and natural scarcities, alongside the limited remaining time to act.

A decade later, authors of the IAASTD report reconvened to document the progress made. One of their key concerns was the continued prioritisation of conventional green revolution and industrial agriculture technologies and practices in public and private R&D investments. Money is not flowing where it should and market structures that support agricultural production modelled after the industrial recipe – with a utilitarian view of nature and a linear external-input-intensive production approach – still prevail.

Institutional gaps persist despite global momentum

Institutional gaps can in part be attributed to the apparent mismatch between agroecology and compartmentalised institutional processes. Rather than prescribing a one-size-fits-all solution, agroecology draws from a broad range of practices and socio-cultural concepts, fostering a holistic yet context-sensitive transformation of food systems. This breadth of applications, spanning across different contexts, constitutes one of the core strengths of agroecology. Paradoxically, this versatility is also what makes the agroecological model both hard to integrate into institutional frameworks and prone to co-optation.

And yet, agroecology is gaining global momentum, driven by a growing body of determined smallholders and family farmers, Indigenous Peoples, civil society actors, policy makers and researchers. They are paving the way for a profound transformation of how food is produced, distributed, consumed and governed; reshaping our relationship with food and the environment, influencing cultural norms, fostering community resilience, and challenging existing economic paradigms. Estimates suggest that about 30% of global agriculture is agroecological, but supportive frameworks which go beyond traditional economic considerations are still critically lacking.

Foundations for Action: harmonising agroecological principles and practices

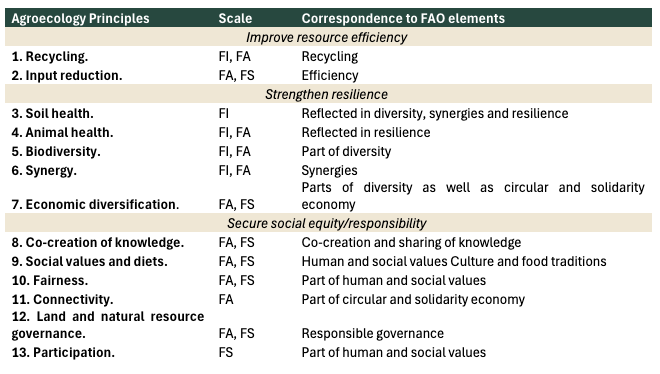

Recent efforts to anchor the social movement, set of practices, and science which define agroecology into an actionable framework have resulted in the definition of the 10 Elements of Agroecology by FAO, as well as the formulation of the 13 Principles of Agroecology by the High-Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) of the Committee on World Food Security (CFS). These parallel processes informed each other while pursuing different aims and applications.

- The 10 Elements of Agroecology, result from an extensive multi-stakeholder process aimed at creating a system redesign framework that can be optimised and adapted to local contexts.

- The 13 Principles of Agroecology, consolidated from literature into normative and causative statements, are designed to guide policymakers.